HOW WE GOT HEREMy name is Greg Carter. I have two siblings and seven first cousins. Together, we are the ten grandchildren of Harriette Jones, who was born in Saint Augustine, Florida, on January 26, 1901.

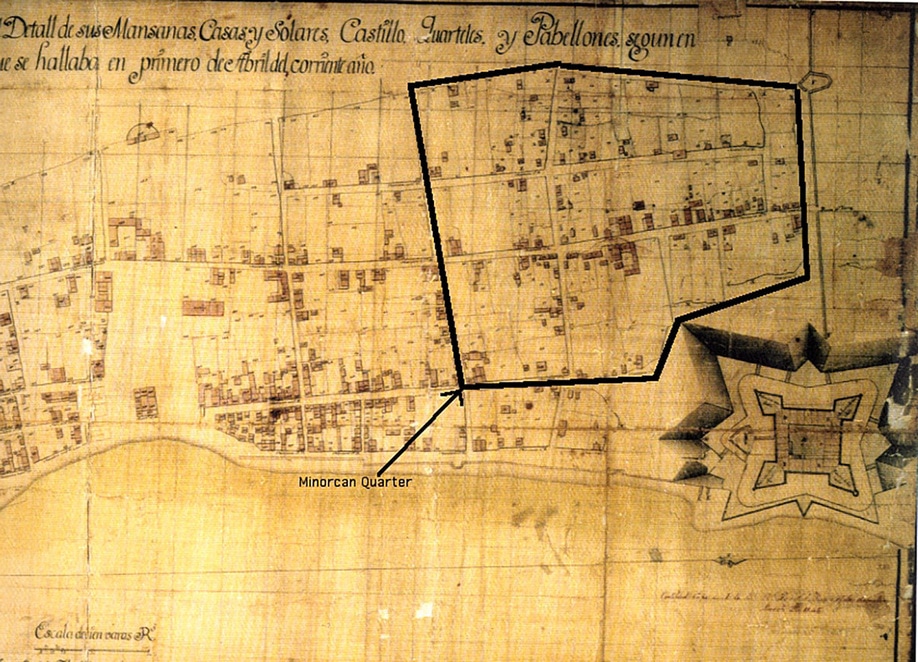

My grandmother's grandparents—Adolphus Pacetty and Amelia Monson—were second cousins, who descended from Mediterranean immigrants who came to New Smyrna, Florida just prior to the American Revolution. The men in this group of travelers were named Pacetty, Leonardy, and Bonelly, and they were all Italian by birth. The women were named Pons, Coll, and Moll, and they were all from Menorca, an island off the coast of Spain. The story of how these individuals came to Saint Augustine is a common one in the region. The infamous expedition that first brought scores of Mediterranean women and men to the New World landed in 1768. Four generations later—in 1867—their off-spring married to close a loop in the family tree that had flourished through a century of colonization, deprivation, political revolution, and civil war. The following recounts the first of those 99 years. A note on spelling and proper names |

|

|

|

|