HISTORY 1858-1978

A Dynasty on Marine Street

|

by Greg Carter

|

revised: Apr/18

|

|

THE CURIOUS CASE OF JESSE FISH

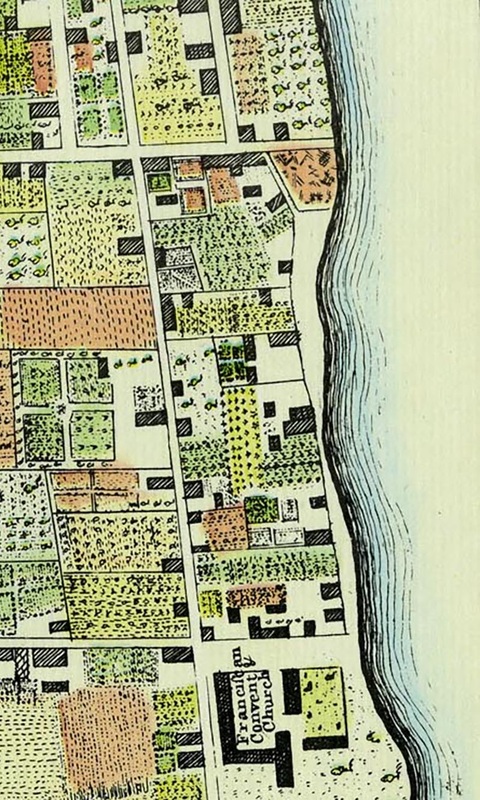

The story behind the construction of 56 Marine Street is lost to history. The property—with a structure on it—appears on the John de Solis Map of 1764, but the laying of its foundation may have been much earlier. The colonial history of the house is enriched by the presence of an enigmatic character in the history of Saint Augustine named Jesse Fish, whose name appears on the chain of titles in 1784 and in 1785. Fish was born in New York in 1726, and moved to Saint Augustine at the age of ten during the first Spanish Period. He learned the Spanish language and cultural customs in the household of the Herreras, a prominent Saint Augustine family, and was raised with the Herreras' son, Luciano. The names of Fish and Herreras appear in odd places and at odd times in the city's history. In 1738, the Spanish royal treasurer Francisco Menendez Marquez, observed that all Englishmen had been banished from Saint Augustine except for a teen-aged Jesse Fish, whose presence was deemed necessary for the procurement of flour and meat from New York. Decades later, Luciano Herreras was one of only eight Spaniards to stay behind in Saint Augustine during the British occupation (1763-1784). Historians associate both Fish and Herreras with spying and other treasonous activities while Britain and Spain were in a state of war. The first of those treasons was smuggling in the autumn of 1762. With the colony short on supplies, Fish teamed with Juan José Elixio de la Puente (another Spanish royal treasurer), and John Gordon, a wealthy merchant from Charleston. Together, they smuggled provisions in from British South Carolina to prevent Saint Augustine from starving. Fish's influence with Puente was exercised again in his most ambitious scheme in 1763. With East Florida ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Paris, Spanish citizens were given eighteen months to sell their property or have it seized by the British Crown. But in that time, few buyers were found. After most Spanish Floridians emigrated to Cuba, Puente returned to Saint Augustine from Havana with a mandate to dispose of the remaining Spanish lots. He found a British population of soldiers with little money, and civilian settlers who expected to receive outright grants of land from the British government. In this inhospitable real estate market, Puente was eventually compelled to transfer all the unsold Spanish property to an agent who would represent owners and reimburse them after the market recuperated. This agent was Jesse Fish. In July 1764, most of the houses, lots, and lands, amounting to almost 200 estates in and around Saint Augustine, were conveyed from Puente to Fish. It was an illicit transaction, and as a British subject Fish was at risk of being charged with treason if it was discovered. Even so, by 1765, Fish controlled the largest accumulation of realty holdings in colonial Saint Augustine—only the Spanish Crown controlled more property in the Floridas. Between 1763 and 1780, Fish transferred the titles of 138 estates, some of which were traded several times. His realty business prospered during 1763–1770 when he sold ninety-five separate pieces of property. Business flourished again in 1774–1778 when British loyalists were moving south from the American colonies, and the Minorcans were moving north from New Smyrna. Saint Augustine was full of refugees in need of housing, and the demand increased property values. One of the lots traded was 56 Marine Street—though that street number would not be assigned for decades. In 1768, the chain of titles shows the property granted to Robert Bisset as #6 Society Block. Bisset was a leading East Florida planter and contractor, who was engaged by the British Crown to extend the King's Road from Matanzas to New Smyrna. This work was substantially complete by 1774, and provided an exodus for the New Smyrna colonists who escaped their indentured servitude in 1777. Bisset is also associated with a 1775 event in which about twenty residents were summoned by Governor Patrick Tonyn to create a battalion of militia—presumably to prepare against the encroachment of revolutionary actions north of Florida. John Moultrie (who later served as Acting Governor) was selected as Colonel, Robert Bisset as Lieutenant Colonel, and Benjamin Dood as Major. It was eventually formed into eight companies but never properly mustered. They also attempted to recruit four black companies.

The fact that a prominent British citizen was awarded 56 Marine Street as a grant from the British government suggests that Fish's claim of ownership was judged inauthentic. That might have been the end of Fish's involvement at 56 Marine, but his name appeared again in the chain of titles when the Second Spanish Period began. Fish's secret compact with Puente had been made in order to prevent the properties from being forfeited to the British at the expiration of the treaty period. However, that sale was not recognized as valid by the Spanish authorities upon their return in 1784. All of Fish's 185 lots reverted to the King of Spain, and were sold at auction on terms very favorable to the purchasers. 56 Marine was traded several times during the twenty year British Period. Bisset actually owned the house for only seven days, selling to John Fairland (1768). Fairland lived there for about ten years, selling to Thomas Hall, who sold to Archibald Brown almost immediately (1778). Nothing is known about Fairland, Hall, or Brown, except that their surnames imply they were British subjects. The next exchange was to Francisco Sanchez in 1785 as the British were evacuating. The seller was Archibald Brown, represented by Jesse Fish. There is nothing in the record that suggests an auction, so perhaps the seizure by the British authority and the grant to Bisset removed 56 Marine from the Fish properties subsequently seized by the the Spanish authority. The fact that Fish returned as a real estate agent for Brown may only prove Fish's substantial reach as an agent and his unique ability to work within both the British and Spanish communities. OCCUPANTS AND NEIGHBORS

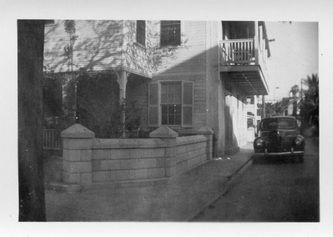

The house that Brown sold to Sanchez on July 18, 1785 was described as a "stone and wood house on Calle Marina." Recorded as Don Francisco Sanchez, the buyer was probably Francis Xavier Sanchez (1736-1807), a shipowner and cattleman. Sanchez and his wife, Mary Hill of Charleston, built the coquina house at 105 Saint George Street which is known today as the Sanchez House. During Sanchez' time, Marine Street was a neighborhood of notables. The adjacent properties—indicated in the 1802 deed of sale—were owned by Antonio Llambias to the north, Don Miguel O'Reilly to the west, and Maria Evans Hudson to the south. Antonio Llambias was a carpenter who built the wood coffin for Governor Enrique White upon his death in 1811. Andres Pacetty, the barber, and Maria Moll (the wife of Josef Bonelly) prepared the body for burial. They may have all known one another, revealing how small the small settlement of Saint Augustine truly was at the turn of the 19th century. The Fernandez-Llambias House is at 31 Saint Francis Street and is today maintained and exhibited by the Saint Augustine Historical Society. Father Miguel O'Reilly was a priest who arrived as part of the convoy that accompanied Governor Vicente Manuel de Zespedes upon the return of Spanish authority in 1784. He was of Irish origin and was in charge of the school founded by his predecessor, Father Thomas Hassett. Father O'Reilly was simultaneously Chaplain of the Army and of the Hospital and, when Father Hassett was transferred as Dean to the Cathedral of New Orleans, Father O’Reilly was designated Vicar of East Florida. He held school in a house at 131 Aviles Street which has been restored and was added to the US National Register of Historic Places in 1974. It is called the O'Reilly House. The properties associated with Llambias and O'Reilly today cannot possibly be those indicated in the 1802 sale—those locations are nearby but are separated by city blocks that haven't been significantly redrawn in two hundred years. These families may have owned multiple Saint Augustine parcels. The southern neighbor's property is more familiar. Mary Evans Hudson was Saint Augustine's best known midwife and had her life fictionalized by Eugenia Price in Maria, published in 1977. She arrived (as Mary Evans Fenwick) as the British were taking over from the Spanish in 1763. Soon widowed, she married Joseph Peavett, the paymaster for the British troops. In 1775, they purchased a home today known as the Gonzalez-Alvarez House (or The Oldest House) at 14 Saint Francis Street, across from the soldiers' barracks. Mary stayed on in Saint Augustine when Spain took Florida back from Great Britain in 1784, and when Peavett died, she married John Hudson. The Hudsons endured financial hardships, ran up debts, and lost their home in 1790. Midwives were probably the closest thing to professional women in Hudson's era. Most midwives were older and childless, and thus available to attend women in labor whenever needed. Many midwives also served as physicians because of their knowledge of the body and experience with persons in discomfort. A midwife was seen in the streets at all times of the day and was often accompanied by a man who was not her husband—possibly the father of the new baby, or a neighbor who came with the alert—which allowed a freedom of movement not experienced by other women. The 1802 sale indicates Mary Evans Hudson was deceased by that time, which is consistent with sources. The idea that the Gonzalez-Alvarez House shared a property line with 56 Marine means that one or both lots were significantly larger than they existed in the 20th century. CROSSING LINES

56 Marine Street was sold by Francisco Sanchez to Jose Dulcet in 1802, though records indicate that Dulcet died that same year—if accurate, there was a 19th century curse on the house, seeing as William Monson also died within twelve months of buying the property in 1858. Dulcet had a daughter named Mary, who was born in Saint Augustine in 1797 and married James (Santiago) Clarke. In a sense, Dulcet and Clarke crossed a battle line, joining a British family to a Spanish family, three years after both European forces were finally excised from the region and Florida became a permanent US colony. But the Clarkes had a history of crossing battle lines and are one of the most intriguing families in the history of the city. To set the stage, one needs to review the revolving door of political authority during the period 1760-1830, a state of perpetual war between Britain and Spain, which was often played out in North America. Santiago Clarke's father was George (Jorge) Clarke. He was a prominent British subject born in British East Florida in 1774, as the territory was becoming a destination for colonists loyal to the crown to escape the American Revolution. In contrast, Jose Dulcet was born in Barcelona in 1760 and immigrated to Spanish East Florida sometime after the war was over and the British were exiled. Jorge Clarke was linked to many of the characters in the 1802 Bonelly family tragedy at Matanzas (see The Raid at Matanzas), as he owned a neighboring plantation, knew King Payne, and apprenticed with the British trading firm of Panton, Leslie & Company. In 1804, he purchased from the Spanish Crown a town lot and buildings located on Marine Street between the military barracks and the old powder magazine. He was a friend and trusted advisor of the Spanish governors of the province from 1811 to 1821, and was appointed to several public offices under the colonial regime, including that of surveyor general. Clarke served in the Spanish militia from 1800 to 1821, defending East Florida against US incursions in the Patriot War of 1812. Clarke owned ten adult working slaves and was among the province's prominent citizens who admitted fathering children by black women, enslaved and free. He lived as husband and wife with Flora Leslie, a former slave whom he had freed, and made their children his heirs, dividing his property among them in his will. Santiago Clarke, then, was the free biracial son of a white man and a black mother. With Mary Dulcet, Santiago had three children named Honora, Susana, and Jorge. Santiago died in 1841. In 1850, a five year-old biracial child named Anna Center was documented as living with her Catholic godmother, Honora Clarke and Honora's white mother, Mary. These people probably all inhabited 56 Marine Street. Monson purchased 56 Marine from Mary Dulcet Clarke, who had inherited the property. The Dulcets owned the house for fifty-six years, but is unclear how long Mary lived there, seeing as she was married in Camden County, Georgia, in 1824. The chain of titles suggests that Mary Dulcet Clarke was deceased at the time of sale in 1858, but other records suggest that she lived to be nearly 100 and died in New Orleans in 1894. At the time of the sale to Monson, two neighboring properties (west and north) were owned by Antonoio Llambias and his family. The south parcel—likely subdivided from the Gonzalez-Alvarez property—belonged to Matias Leonardy. Matias Leonardy was the first cousin of Laureana Leonardy who was married to William Monson. A sixty-five year old Antonia Paula Bonelly (Laureana's mother and Matias' aunt) was living at this Marine Street property with Stephen and Jane Lacy in the 1850 Federal Census. Jane Lacy was Laureana Leonardy's younger sister. CHAIN OF TITLE

FAMILY AT 56 MARINE STREET

|

|

1858 1862 1867 1876 1885 1895 1906 1916 1932* 1944* 1953* 1965* 1975 |

New arrivals underlined

Family purchases 56 Marine Street; 4 adults, 5 children (16 or younger): William Monson (46), Laureanna Leonardy (42), Amelia Monson (19), William Monson (17), Carolina Monson (13), Jane Monson (12), Fritzard Monson (9), Catherine Monson (7), Anthony Monson (4) William and Caroline die, Laureanna's mother Antonia Paula moves in, young William goes to war; 3 adults, 4 children: Antonia Paula Bonelly (76), Laureana Leonardy (46), Amelia Monson (23), Jane Monson (16), Fritzard Monson (13), Catherine Monson (11), Anthony Monson (8) Amelia marries and husband moves in; 6 adults, 2 children: Antonia Paula Bonelly (81), Laureanna Leonardy (51), Adolphus Pacetty (38), Amelia Monson (28), Jane Monson (21), Fritzard Monson (18), Catherine Monson (16), Anthony Monson (13) Antonia Paula dies, four adult Monson children move out, three Pacetty children are born; 3 adults, 3 children: Laureana Leonardy (60), Adolphus Pacetty (47), Amelia Monson (37), Amelia Pacetty (8), Ellen Pacetty (5), Cassia Pacetty (3) Cassia dies, Phillip adopted; 4 adults, 2 children: Laureana Leonardy (69), Adolphus Pacetty (56), Amelia Monson (46), Amelia Pacetty (17), Ellen Pacetty (14), Phillip Murphy (10) Laureanna dies, both Pacetty girls marry and husbands move in, father-in-law Richard moves in; 8 adults: Adolphus Pacetty (66), Richard Jones (62), Amelia Monson (56), Amelia Pacetty (27), Thomas Dowd (27), Ellen Pacetti (24), Harry Jones (22), Phillip Murphy (20) Richard dies, four children are born; 7 adults, 4 children: Adolphus Pacetty (77), Amelia Monson (67), Amelia Pacetty (38), Thomas Dowd (38), Ellen Pacetti (35), Harry Jones (33), Phillip Murphy (31), Charlotte Jones (10), Mabel Jones (9), Harriette Jones (5), Mildred Jones (0) Adolphus and Phillip die; 7 adults, 2 children: Amelia Monson (77), Amelia Pacetty (48), Thomas Dowd (48), Ellen Pacetti (45), Harry Jones (43), Charlotte Jones (20), Mabel Jones (19), Harriette Jones (15), Mildred Jones (10) Thomas dies, Harriette marries and moves to North Carolina; 7 adults: Amelia Monson (93), Amelia Pacetty (64), Ellen Pacetti (61), Harry Jones (59), Charlotte Jones (36), Mabel Jones (35), Mildred Jones (26) Amelia (mother), Harry, and Amelia (daughter) die; 4 adults: Ellen Pacetti (73) Charlotte Jones (48), Mabel Jones (47), Mildred Jones (38) Ellen dies; 3 adults: Charlotte Jones (57), Mabel Jones (56), Mildred Jones (47) Mildred dies; 2 adults: Charlotte Jones (69), Mabel Jones (68) Mabel dies, Charlotte relocates to North Carolina *After 1936, Fleming Bel is a regular fixture at the house during social times and meal times, and might be counted as an additional resident. Bel is the partner of Mildred Jones, but his sleeping quarters are in an apartment directly across the street. Bel died in 1970. |

THE END OF AN ERA

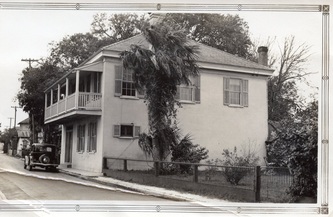

The beginnings of my personal study of genealogy began in 1978. My aunt, Mabel Jones, passed away in July 1975, and after the memorial, the family's greatest concern was relocating her sister Charlotte—affectionately known as Old Lady during most of her life. Since birth, Old Lady had suffered from an undiagnosed developmental disorder which left her with reduced motor skills. As she aged, she became mostly invalid. She could only walk with assistance, she had almost no dexterity in her fingers, and her speech was slurred.

For several years prior to 1975, the three surviving Jones sisters (Charlotte, Mabel, and my grandmother, Harriet) were seasonally shuttling between Saint Augustine and Harriet's house in High Point, North Carolina. Harriet had married and moved in 1931, but was widowed in 1970. With Mabel now gone, it was decided that Grandma and Old Lady would now permanently move to High Point, where my aunt and uncle were within driving distance. Old Lady was seventy-nine years old at the time. Grandma was seventy-four and beginning to show signs of dementia that would plague her until her death in 1987.

The younger generations were aware of the historical significance of 56 Marine Street, which at this point had been a family homestead for 117 years. But the septuagenerian Jones sisters were the last to have deep roots in Florida. Harriet's generation was born around 1900, and she was the only one of her sisters to marry. She moved north and had three children between 1932-1940, but they were firmly established elsewhere by the 1970s, with professional lives, and young children of their own. My generation was born between 1957-1970, with my oldest cousin, Lisa, only eighteen years old and starting college in 1975. At that instant, there was no one at a transitional time of life with prospects of carrying on the family legacy in Saint Augustine.

56 Marine Street was shut tight for almost three years, while the health of the human generation took precedence over the maintenance of the property. The delay also allowed my parents, aunts, and uncles to weigh their options—including the physically and emotionally demanding option to sell.

On a school break in February 1978, my family flew to Saint Augustine with a one-week assignment to clean-out personal memorabilia and valuables from 56 Marine Street. Concerned about the condition of the shuttered house, we stayed at the Bayfront Inn around the corner. My brother, sister, and I were between the ages of seven to thirteen. We were of limited use in sorting the family possessions, and were mostly given license to play in the city which was not yet the tourist destination it is today.

At some time during that week, my mother showed me a box of papers that included some genealogical research from the Saint Augustine Historical Society. These included typewritten genealogies of the Minorcan ancestors: Bonelly, Pacetty, and Leonardy. In some cases, we had carbons of the raw information, in others, a family member (often Mabel) had composed a narrative around the history—possibly as a school assignment. My mother showed me how to get to the Historical Society research library, which was located at that time behind the The Oldest House Museum, only a few yards from 56 Marine. I met the librarian, Eleanor Barnes, who had been a friend of all the Jones' sisters (actually a distant relative), and had helped compile most of the Minorcan genealogy we had discovered.

When we returned to Boston, the most glamorous story from the history was the mysterious life of Richard Henry Jones. We had possession of a dozen or so letters written from Saint Augustine to sources in England seeking information. These were entirely fruitless, and they revealed to me that the case was still open. I started writing to British Consulates and some Public Record Houses in England when I was only fifteen years old. Ms Barnes continued to be a source of information and advice, as did my Aunt Mae Kirkman, who started me on the path of my grandfather's genealogy in North Carolina.

Meanwhile, the family had completely vacated the Marine Street House by 1979. It was put on the market and sold to Anthony DiFiore, who was committed to its restoration.

The beginnings of my personal study of genealogy began in 1978. My aunt, Mabel Jones, passed away in July 1975, and after the memorial, the family's greatest concern was relocating her sister Charlotte—affectionately known as Old Lady during most of her life. Since birth, Old Lady had suffered from an undiagnosed developmental disorder which left her with reduced motor skills. As she aged, she became mostly invalid. She could only walk with assistance, she had almost no dexterity in her fingers, and her speech was slurred.

For several years prior to 1975, the three surviving Jones sisters (Charlotte, Mabel, and my grandmother, Harriet) were seasonally shuttling between Saint Augustine and Harriet's house in High Point, North Carolina. Harriet had married and moved in 1931, but was widowed in 1970. With Mabel now gone, it was decided that Grandma and Old Lady would now permanently move to High Point, where my aunt and uncle were within driving distance. Old Lady was seventy-nine years old at the time. Grandma was seventy-four and beginning to show signs of dementia that would plague her until her death in 1987.

The younger generations were aware of the historical significance of 56 Marine Street, which at this point had been a family homestead for 117 years. But the septuagenerian Jones sisters were the last to have deep roots in Florida. Harriet's generation was born around 1900, and she was the only one of her sisters to marry. She moved north and had three children between 1932-1940, but they were firmly established elsewhere by the 1970s, with professional lives, and young children of their own. My generation was born between 1957-1970, with my oldest cousin, Lisa, only eighteen years old and starting college in 1975. At that instant, there was no one at a transitional time of life with prospects of carrying on the family legacy in Saint Augustine.

56 Marine Street was shut tight for almost three years, while the health of the human generation took precedence over the maintenance of the property. The delay also allowed my parents, aunts, and uncles to weigh their options—including the physically and emotionally demanding option to sell.

On a school break in February 1978, my family flew to Saint Augustine with a one-week assignment to clean-out personal memorabilia and valuables from 56 Marine Street. Concerned about the condition of the shuttered house, we stayed at the Bayfront Inn around the corner. My brother, sister, and I were between the ages of seven to thirteen. We were of limited use in sorting the family possessions, and were mostly given license to play in the city which was not yet the tourist destination it is today.

At some time during that week, my mother showed me a box of papers that included some genealogical research from the Saint Augustine Historical Society. These included typewritten genealogies of the Minorcan ancestors: Bonelly, Pacetty, and Leonardy. In some cases, we had carbons of the raw information, in others, a family member (often Mabel) had composed a narrative around the history—possibly as a school assignment. My mother showed me how to get to the Historical Society research library, which was located at that time behind the The Oldest House Museum, only a few yards from 56 Marine. I met the librarian, Eleanor Barnes, who had been a friend of all the Jones' sisters (actually a distant relative), and had helped compile most of the Minorcan genealogy we had discovered.

When we returned to Boston, the most glamorous story from the history was the mysterious life of Richard Henry Jones. We had possession of a dozen or so letters written from Saint Augustine to sources in England seeking information. These were entirely fruitless, and they revealed to me that the case was still open. I started writing to British Consulates and some Public Record Houses in England when I was only fifteen years old. Ms Barnes continued to be a source of information and advice, as did my Aunt Mae Kirkman, who started me on the path of my grandfather's genealogy in North Carolina.

Meanwhile, the family had completely vacated the Marine Street House by 1979. It was put on the market and sold to Anthony DiFiore, who was committed to its restoration.