HISTORY 1778-1802

Spoils of War

|

by Greg Carter

|

revised: Apr/18

|

|

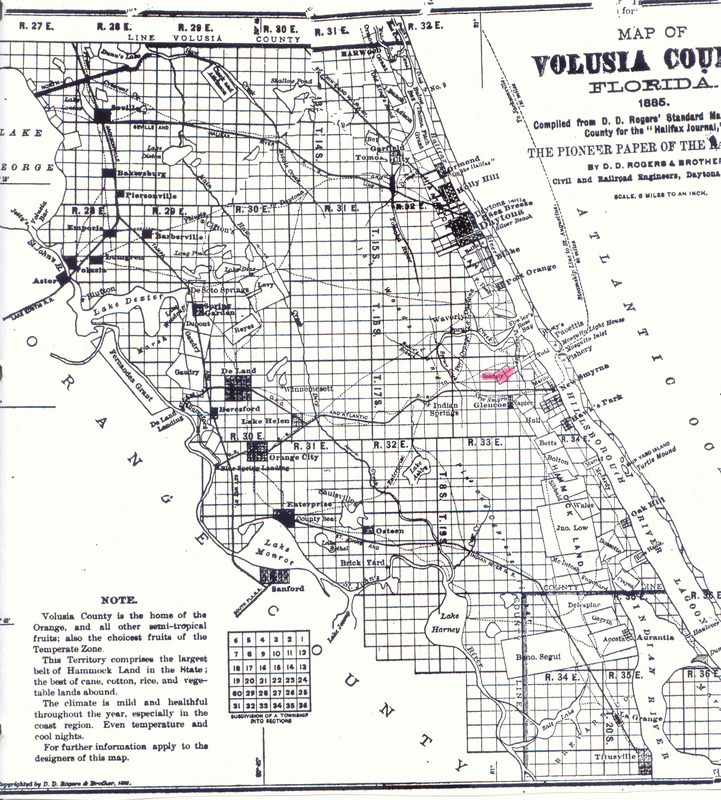

The second half of the 18th century was a politically volatile time in the New World, and particularly in the Florida colonies. In 1763, the British acquired East Florida as spoils of war in a treaty with both Spain and France, ending 250 years of Spanish rule. 1300 Spanish residents of Saint Augustine evacuated to Cuba, Mexico, and the West Indies. British colonial venture—like that of Dr Andrew Turnbull in New Smyrna—were encouraged to quickly populate the territory, but many of these failed, leaving Saint Augustine with a population of Mediterranean refugees collectively known as the Minorcans. While Britain's more northern Atlantic colonies declared their independence and engaged in an eight-year revolutionary war, Florida became a safe harbor for British loyalists. Then a pawn in another treaty.

In May 1781, British colonials in East Florida received the unwelcome news that the neighboring colony of West Florida had fallen to Spanish forces allied with the Americans. Although there had been little contact between the two colonies, the fact that Pensacola was now in the hands of an enemy was a disturbing turn of events. In October of that same year, word arrived from Virginia that Lord Charles Cornwallis had surrendered his entire British army to American General George Washington and the rebels. The United States was born, and in recognition of their aggression against a common enemy, Spain was granted governance of East Florida in the Treaty of Paris of 1783. The British were forced to sell or leave their homes in Saint Augustine, but most Minorcans who had escaped New Smyrna decided to stay. Many of them spoke a form of Spanish, they were Catholic, and after suffering abuse by British nobles, the Minorcans had little difficulty publicly swearing allegiance to the Spanish Crown. In June 1784, Governor Vizente Manuel de Zespedes and 500 Spanish soldiers arrived from Cuba to take over the colony. In November, the last refugee ship departed carrying Governor Patrick Tonyn, his staff, and the few remaining British subjects away to England. Within weeks, the bustling economic activities of Saint Augustine ended and the town returned to serving as a remote outpost of the Spanish Empire. The population of Saint Augustine decreased from 17,000 to about 3,000, with the majority being the Minorcans. Less than 100 British subjects had abandoned their allegiance to King George in order to continue living in Spanish Florida. Saint Augustine's so-called Second Spanish Period was a era of governmental neglect. There was no new settlement, only small detachments of soldiers, and the existing fortifications decayed. |

|

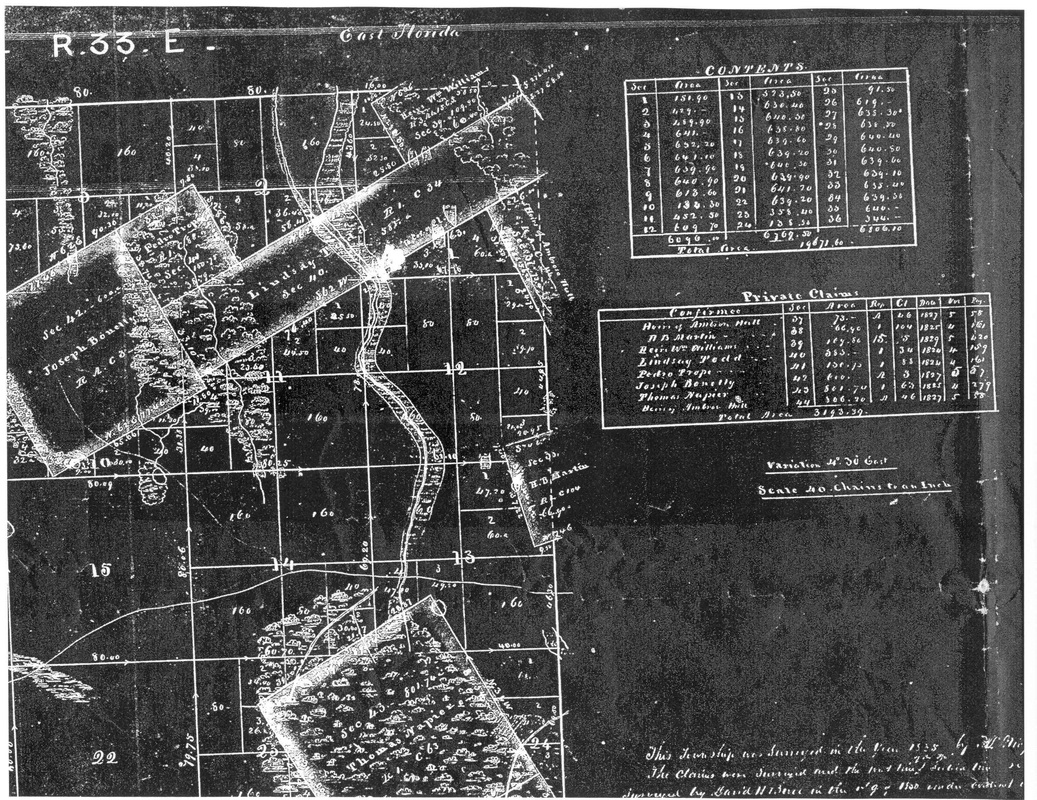

ATTACK AT MATANZAS INLET

After escaping Dr Turnbull's servitude, some Minorcan farmers returned to the southern region to cultivate land under new circumstances. The most prominent Minorcan plantation owner was Francisco Felipe Fatio, who Josef Bonelly and his family was living with at the time of the 1787 East Florida Census. In September 1796, Bonelly himself was granted 600 acres at Turnbull Bay by Spanish Colonial Governor Enrique White. Later, he received an additional 600-acre plantation near Matanzas Inlet, where his neighbors were Josiah Dupont and Francisco Pellicer. Bonelly also owned ten acres at the North Wharf of the River Mosquitos. In January 1802, Antonia Paula Bonelly was fifteen years old and living on her father's plantation at Matanzas with her parents and five siblings: her adult brother Tomas (25), and four children (between 1 and 14 years of age). Her eldest sister, Maria Catarina Bonelly, had married Tomas Pacetty in 1801, and now lived in the city. At around three o'clock in the afternoon of January 21, a war party of nine Miccosukee raiders attacked the Bonelly plantation at Matanzas. Josef Bonelly was away from the property, but his son Tomas was murdered—by one account slain in the fields where he was working, by another, tied with cords, scalped, and burned at his father's house at the wharf. Testifying in 1835, an old citizen recalled seeing the dead body of Tomas Bonelly laid in the marketplace in Saint Augustine after being brought to town in a boat. The Miccosukee spared the others but claimed them as hostages. The nine Indians set out immediately with all the plunder that they and the prisoners could carry, and travelled by a circuitous route for the interior of the country. The family was forced to march that day and the following night until dawn, when they halted and encamped for twenty-four hours. The party could not travel fast, as the stolen goods were heavy, and Antonia Paula and her sister Catherine, who was eleven, were obliged to carry the baby Juan, who was about twenty months old. On the second day after they started from Matanzas they crossed a small river, and afterwards they crossed the Saint Johns River where it was very wide, probably a small lake. When they reached the river Suwannee, they crossed in a skin stretched out by two cross sticks, and a rim made of wood. In telling the story, Antonia Paula remembered that she laid very still in the bottom while crossing, afraid to look up, as the banks of this river were very steep and the crossing very dangerous. After twenty-four days of travel, they reached their eventual destination: the town of Miccosukee, located along the boundary of Spanish East and West Florida (about twenty miles northeast of present-day Tallahassee). The Spanish considered this area west of the Suwannee River under West Florida jurisdiction managed at Pensacola. But Miccosukee was a day's journey from the Spanish outpost at Saint Marks and considerable distance still from Apalachicola, leaving it isolated from access or communication. Antonia Paula later testified that the Chief was named Ken-ha-jah, but he was almost certainly Kinache, who was known by many names including Kinhega, Kinheja, and Kinhija—all of which could be understood as Ken-ha-jah. Born in 1750, Kinache was prominent among the Seminoles along the mouth of the Apalachicola River during the late 18th century when he allied with Britain during the American Revolution. Following Britain's defeat, Kinache moved to the Miccosukee village on the west side of Lake Miccosukee where he lived among the Seminole of western Florida. The party halted a short distance from the town, where they made a division of their plunder. The Bonelly prisoners were turned over to some Indian women who came out to meet them. In her deposition, Antonia Paula recounted cruelties, including an Indian dance over the scalp of Tomas. She explained to the court that "her trials were very severe; and the circumstances and history of her captivity and that of her family were so peculiar and barbarous that everything appears to be fresh to her mind, and she does not think that anything but death can efface them from her memory." The details of the Bonelly's captivity are unknown. Clearly, Antonia Paula was raped, as when she was returned to her family, she was pregnant with a Miccosukee medicine man's child. Catherine's trials are purely speculative, but the ordeal may have shortened her life. Rescued in the summer of 1802, Catherine died in September 1803 at the age of twelve. It took seven months before a trader trusted by the Miccosukee, named Jack Forrester, was sent to rescue the family. Forrester worked for a Scottish firm named Panton, Leslie & Company, founded in 1783 for the purpose of trading with the Indians of Florida. The partners were British loyalists during the American Revolution and had been forced out of the United States with their property confiscated. Having established themselves in Florida and the Bahamas, the company was able to continue operating in Florida after its return to Spanish rule because there were no Spanish traders established in trade with the natives. The partners harbored a great antipathy toward the United States and used their influence with the Indians to both advance Spanish territorial claims against the US, and to encourage the Indians to resist white settlers and US attempts to acquire land from the tribes. Acting as emissary in the summer of 1802, Jack Forrester bought the freedom of Maria Bonelly, and her three youngest children for $300 ransom. But the sum was deemed insufficient for the teen-agers, Antonia Paula and Josef, and they remained. In the weeks that followed Forrester's mission, fourteen year-old Josef escaped the Miccosukee and hid in the surrounding woods and swamps. He made it to Saint Marks on the Gulf of Mexico where military commanders had him sent to Pensacola, Mobile, New Orleans, and eventually Havana. In Cuba, Josef had the good fortune of spotting a family friend (in fact, his godfather), Captain Steven Benet, who was able to transport him home to Saint Augustine. An original Turnbull colonist himself, El Capitan Estevan was the husband of Catalina Hernandez, a Matanzas plantation neighbor, and a native of Arabel of San Felipe—the same colony as Josef Bonelly's father. Benet was the grandfather of the well-known American poet, Steven Vincent Benet—who fictionalized the story of the Turnbull colony in a novel called Spanish Bayonet. In 1803, Josef Bonelly Sr sold his Matanzas holdings to Gabriel W Perpall and gathered the remaining ransom. Twenty-two months after the original attack, he sent his son-in-law Tomas Pacetty with $200 to gain freedom for Antonia Paula. Pacetty traveled with Payne, an Indian interpreter, and a negro slave. The venture was successful, but the celebration was subdued. Antonia Paula had been held by the Miccosukee medicine man as a mate, and weeks after returning to Saint Augustine, she gave birth to a girl that was baptized Maria Antonia. The girl lived nine or ten years. She died around the same year as Antonia Paula's father, who passed in 1811 at the age of 54. Josef Bonelly had been financially ruined by the raid on his property, and there is no evidence of how he supported himself after selling his farm. Bonelly owned property in Saint Augustine—a wooden house located north/south between Hypolita Street and Baya Lane, and east/west between Charlotte Street and the bay. Antonia Paula, meanwhile, married Bartolome Leonardy in 1808—while her Indian daughter was still living—and had a large family, about half of whom would become early settlers of Tampa. Leonardy was the son of one of the most prominent Minorcan businessmen in Saint Augustine, Don Roque Leonardy. Antonia Paula's sister Maria and brother in-law Tomas Pacetty did not remain in Saint Augustine for long. They settled in Saint Marys, Georgia, around 1808, where Tomas drowned in a fishing accident in 1813. Antonia Paula participated in a claim to regain the value of her father's lands in 1835, after which the US Commissioners decreed that "Joseph Bonelly, having been made prisoner of the Seminoles and his property destroyed, had no chance to protect his title." It is clear the family did not recover the land, but they may have received a cash payment. At a much later date, in 1893, the Bonelly heirs fought for their land rights by filing a claim to receive proper title for the property at Turnbull Bay and North Wharf granted in 1796. This appears to have been a fruitless attempt to profit from the expansionist efforts of railroad magnate Henry Flagler, whose Florida East Coast Railway passed through Matanzas. Antonia Paula lived through the American Civil War, and died in 1870 when she was 84 years old. She last lived at the house of her daughter Laurenna Leonardy at 56 Marine Street. AFTERWARD

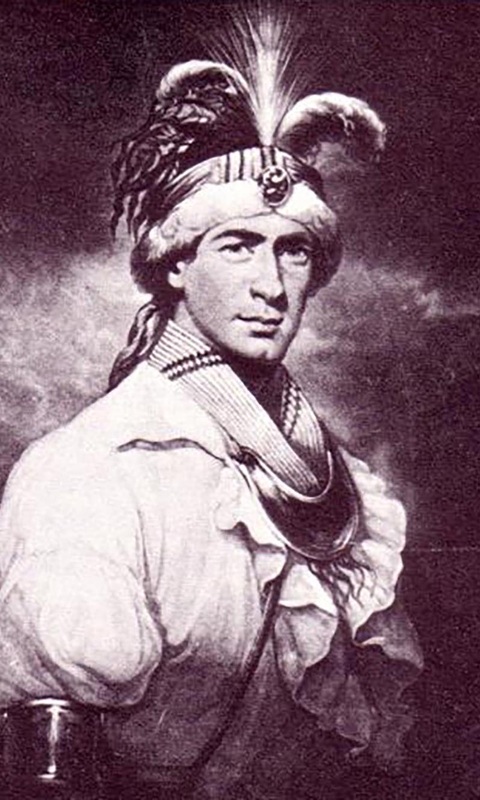

Payne, the Indian interpreter who gained Antonia Paula's release was a significant Native American leader. Called King Payne, he was the son of the Seminole high chief Ahaya (Cowkeeper) and succeeded him in leading the Seminoles upon Ahaya's death in 1783. He led his people against the Spanish and American invasion from Georgia, then established a number of towns and villages, including Paynes Town in Paynes Prairie, both of which are named for him. The attack on the Bonelly plantation was not random, and it had political roots in the decades-long struggle between Native, Spanish, British, and American interests in Florida. King Payne told Jack Forrester that a small party of Indians had set out with the intention of plundering the inhabitants of the coast. Forrester was concerned that the Spanish defenses along the Saint Johns were relaxed and that even small Indian forces--like the nine-man Miccosukee war party—could not be repelled. Planters, like Bonelly, were increasingly anxious about their exposed position. Raids like these were ordered by a peculiar figure in Native American history, William Augustus Bowles. A white man, Bowles was born in Maryland just before the Revolution. He joined the British army and then deserted to take up arms with the Creek Nation near Pensacola. After the war, Bowles became a major thorn in the side of Forrester's trading firm, Panton, Leslie, & Company, who had been granted a trade monopoly with the southeast tribes. Pursuing the idea of an American Indian state, Bowles built an alliance between the Creek, Cherokee, and Seminole, and in 1800 declared war on Spain. Bowles operated two schooners and boasted of a force of 400 frontiersmen, former slaves, and warriors, whose primary activities involved piracy. Forrester and King Payne's direct involvement in the Bonelly negotiations show that larger forces were at play in this event than simply the safety of a fifteen year-old girl. Panton had a robust commercial enterprise in Florida that had withstood the political change of authority from Britain to Spain, but was now at risk because of a lack of security. On paper, Forrester and Bowles might be seen to have been cut of the same cloth. They were both British loyalists opposed to American independence, and inconvenienced (at best) by the return of Spanish authority to Florida. They each had earned the genuine trust of the tribes, and exerted influence on Indian leaders. The balance of allegiances was complicated for the tribes. While Bowles appealed to Indians with calls for nationalism, Forrester was the key access point to essential European commodities: in particular, weapons and rum. Panton supported Indian resistance against Spanish incursions and the imminent invasion of the United States, but not if that resistance included the disruption of Panton's monopoly by insurgents like Bowles. Payne's forewarning of the Miccosukee raid suggests that by 1802, he had placed his bets with Forrester. They were each involved in rescue missions on behalf of the Bonellys: first to save the wife and small children, and then to secure Antonia Paula. It may be notable that Forrester's first attempt was not fully successful (he brought back only four of the six captives). In addition to seeking more ransom, the Miccosukee needed the Seminole Chief to intercede directly. It may also be notable that by the time of the Payne mission, Bowles had been captured by the Spanish and died in Cuba. Unfortunately, the devastation to the Bonelly family did not lead to improvements in Spanish colonial supervision. Spain itself was the scene of war between 1808-1814 and exerted little control in Florida. Natives were recruited by both sides in the War of 1812, and battles were fought in Florida between British and American forces with the indifference of the Spanish governor. Over the years, all sides lost control of this balance. Tribes trading with Panton incurred enormous debts. To make good they sold millions of acres of land—parts of Alabama and Mississippi—to the United States, using the proceeds to pay off those debts. The British were permanently ousted by the second failed war, and rather than bolster British interests against the US, Panton indirectly paved the way for cheap American expansion through Indian territory. For their part, the Spanish moved from indifference to abandonment. In 1821, the Adams–Onís Treaty peaceably turned the Spanish provinces in Florida over to the United States. At the time of the hand-over, there were only three Spanish soldiers still stationed in Saint Augustine. |