MEMOIR 1931-1947

Marine Street in the 20th Century

|

by Thomas Carlton Kirkman Jr

|

revised: Apr/18

|

|

The following is derived from a memoir written by my uncle Thomas Carlton (Sonny) Kirkman Jr about his childhood, and stories told to him by his mother and aunts about life in Saint Augustine in the first half of the twentieth century. For the sake of this narrative, I have removed Sonny's first person narrator and added historical references. To read the original text, please go to A Childhood Memoir 1934-52.

Harriet Jones defied a family tradition in 1931, when she married and moved out of the house at 56 Marine Street. Her mother and aunt had both welcomed husbands into the household in 1895 and 1896, as had her grandmother as far back as 1867. When the youngest of her sisters, Mildred Jones, was born in 1906, there were no fewer than eleven people (seven adults) living in the three-bedroom house. Two generations of children had produced only daughters, and the husbands to these daughters were the only men in the crowded household.

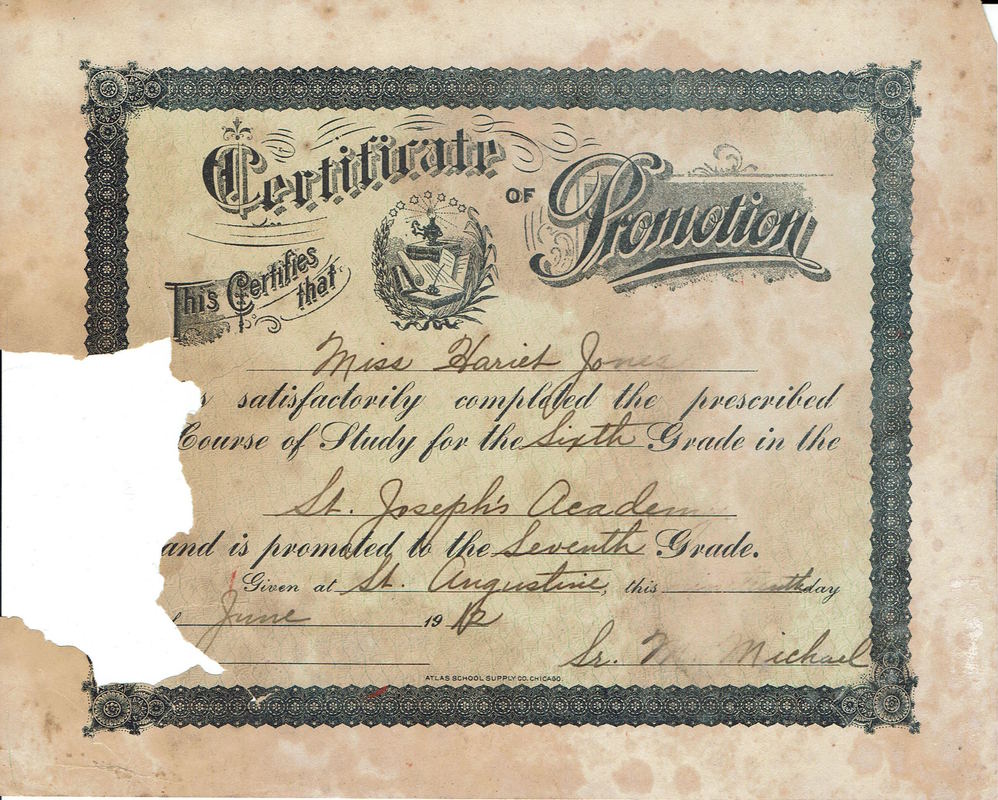

Harriet (born in 1901) grew up in Saint Augustine at the turn of the twentieth century. It was predominately a Catholic city with a Cathedral and a large convent of nuns from the Order of Saint Joseph. Harriette and two of her sisters attended school at Saint Josephs Academy, on Saint George Street adjacent to the convent, and just a few blocks from their home. Harriet's oldest sister was Charlotte Jones, who was known as Shirley almost as soon as she was born. Shirley suffered from a crippling disability that made it hard for her to walk, to use her hands with any dexterity, or to speak clearly. She was never educated, and many people assumed she had a mental disability, though family members knew that not to be the case. Harriet's son, Sonny Kirkman, remembered Shirley as possessing "a brilliant mind and an unbelievable memory." He wrote, "I think she was the most remarkable person I have ever known." Shirley's welfare played a major part in the future of the Jones family. Harriet took up the violin at a very early age and started seriously studying music in her teens under a instructor named Vincent Amato. Amato lived in Jacksonville but because he thought highly of Harriette's talent, he regularly traveled to Saint Augustine to give her lessons. After she graduated from high school, Amato wanted her to move to Jacksonville where he felt she would have more opportunities at pursuing a musical career. Harriette declined, feeling that she had responsibilities at home helping with the support of the family and caring for Shirley. It was a decision that she reflected on later in life with some regret. |

|

In the early 1900s, Florida blossomed as a major tourist area. Wealthy northerners would winter in Florida and many built winter homes there. In 1885, railroad magnate Henry Morrison Flagler had built the Ponce de León hotel in Saint Augustine among a network of Florida destinations. By 1900, he sought to support this network with a railroad that ran down the east coast of Florida from Jacksonville to Key West, with further transit to Havana. Flagler purchased several small railroads that were already in service, widened them, connected them, and added an additional line over the water between Miami and Key West. He called this the Florida East Coast (FEC) Railway and set the headquarters in Saint Augustine.

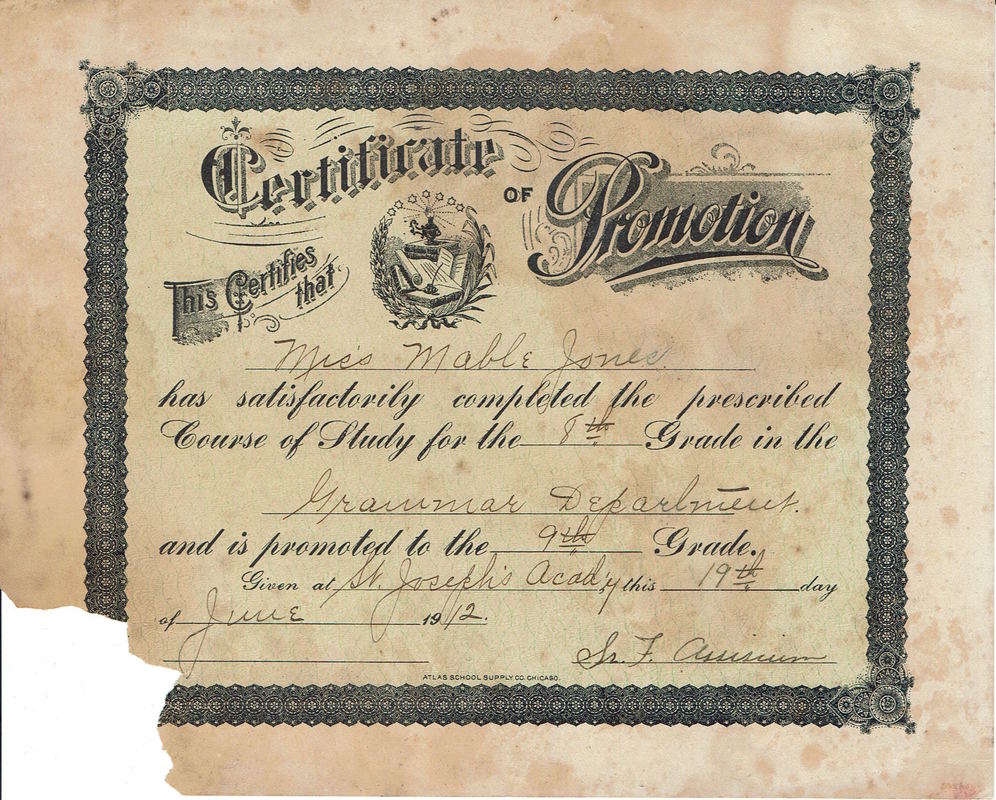

Mabel and Mildred Jones went to work at the FEC after they graduated from Saint Josephs. Harriette took an additional stenographers course which enabled her to land a better position at the FEC after high school, around 1920. During this time, Thomas Carlton (TC) Kirkman was growing up in High Point, North Carolina. He studied engineering at Trinity College (later Duke University) in Durham, and began work as a land appraiser with the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) around 1927 or 1928. His work took him to Saint Augustine for the first time working on an ICC project with the FEC. The project was to locate property along the railroad that would be suitable for industries in hope that Florida could develop a stronger industrial base. Harriette used to say that TC walked from Jacksonville to Miami along the railroad. Kirkman developed a relationship with the Jones girls and their family while based in Saint Augustine at the FEC headquarters. When he asked Harriette to marry him, she was faced with a difficult decision. She knew the ICC project Kirkman was working on was ending, and he would need to relocate to follow the next job. She allowed him to win the argument. They were married on July 4, 1931, in the family home at 56 Marine Street. After the Kirkmans married, TC's work took them to a number of places for short periods of time. They lived in Lakeland, Florida, and then Bluefield, West Virginia. They eventually ended up in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where their daughter, Shirley Kirkman (named for aunt), was born on May 2, 1932. Later, they returned to Saint Augustine, and lived in an apartment house on Marine Street directly across the street from Harriette's family home. Sonny was born May 26, 1934, at the FEC hospital. The bill covering all the expenses of his birth amounted to $55. The family of four moved to Miami, and were there during the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 that destroyed Flagler's railroad to Key West, which was never restored. They briefly lived in Saint Augustine again until Kirkman left the ICC in 1936 for reasons not entirely understood. His government project may have simply ended, and he was laid off. But he might have also been lured home by family struggling in High Point during the Great Depression. He gave up engineering for a time and joined his father at the Moffitt Furniture Store. In the fall of 1936, TC and Harriette bought a house in High Point at 902 Sunset Drive. Harriette stayed in touch with her family by routinely writing letters. For Shirley and Sonny, getting a letter from Saint Augustine was something to look forward to. Harriette could predict the arrival based on when she had last written. The children's grandmother, Nellie (Ellen Pacetty), was the primary correspondent, and when the letter came, Harriette would read it aloud. At the end of every letter, there would be a note from their grandfather, Harry, and two dimes—one for Shirley and one for Sonny. Like his mother, Sonny showed musical promise at a young age. His aunt on his father's side, Elizabeth Mae Kirkman, was classically trained and offered piano lessons to dozens of children in High Point. Mae noticed that Sonny could—at only four or five years old—pick out melodies using all of his fingers, as opposed to using only a single finger. This inspired her to teach him to read music. After moving to High Point, the Kirkmans continued to visit Saint Augustine, while the Jones' ventured north only occasionally. After young Shirley started school, trips could only be made in the summer. Harriette and her children stayed in Florida for the whole season, and TC would join for a week at a time. Travel was by train—the most reliable and affordable option of the period, and also an industry which TC Kirkman reconnected with in the late thirties. To get to Saint Augustine from High Point, one started in Sanford, North Carolina, to use the Seaboard Railroad, or in Fayetteville to travel via the Atlantic Coast Line. The luggage was all shipped ahead, except for one suitcase containing the items the family would need while on the train. They traveled in a Pullman sleeping car for an overnight trip. It was about twelve or thirteen hours to Jacksonville. |

|

When they arrived in Jacksonville, two or three of the relatives would be there to meet them and drive them to Saint Augustine. The driver was often Fleming Bel, who was the partner of Harriette's sister Mildred. Born in 1891, Bel had come to Saint Augustine via Savannah in the mid-1930s. He lived in a very small apartment about a half block down from 56 Marine. While looking for a job, he met Harry Jones and asked if he would take him on as a house painter until he found something more permanent. The men became great friends.

Having worked at one time as a Pullman conductor, Bel was eventually able to get work at the FEC in the offices of the passenger division. He knew that his neighbors and co-workers, Mabel and Mildred, went home from noon to 1pm for lunch every day. He offered to drive Mabel and Mildred to and from work since he lived so close. In return, they invited him to share lunch with them, and after that, Bel became a permanent guest for the noon meal—the biggest meal of the day. During one of the Kirkmans' early visits to Saint Augustine, Sonny remembers that he and Shirley caused some names to be changed among their aunts. Mabel became Auntie, Mildred became Bunny, and their sister Shirley became Old Lady. Because of her disability, their crippled aunt was never able to play with the children as much as they liked. On one occasion they insisted she dance, but another family member excused her by joking that she was "just an old lady". Rather than being humiliated, the elder Shirley thought the idea was so funny that she shared it with everyone. She began to opt out of anything she didn't want to do by saying she was an old lady. In short time, it became Shirley Jones' family nickname. Young and old called her Old Lady until the day she died. Old Lady was severely handicapped, but she was not completely invalid. In middle age, she could walk, and even go up and down stairs by herself if she supported her weight on the railing. She could feed herself, though her limited dexterity meant she could only use a spoon—someone, usually her mother, Nellie, cut everything for her. Old Lady dressed herself, although she had trouble with buttons, particularly if they were small. She was determined to do things herself and dealt with her challenges with stubborn persistence, even if working a button required ten minutes. When Old Lady needed help, she showed her disappointment. She hated to burden anyone. Her speech was hard to understand, though not for those who became accustomed to it. There were times when she would replace troublesome words with phrases people could more easily decipher—similar to the way a stutterer or foreign language speaker might seek easier vocabulary. Old Lady sometimes would make a game out of story-telling, asking children to name what she was describing, then ask for words that rhymed. Eventually, the listener would hit upon the word she was struggling to say. Sonny described this as a kind of charades, but with words instead of actions. At times, Old Lady was the family comedian, and at times she was just eccentric. She inexplicably called Fleming, "Andy" and named Sonny, "Bubba". In the thirties, 56 Marine was a large, square, two-story house, which sat with only the sidewalk between it and the street. There was a covered porch that ran completely across the front of the second floor and protruded out over the sidewalk below. The porch had a swing and three rocking chairs. The house on the other side of the street had a clear side yard which allowed a view of Bay Street, the sea wall, the Matanzas River, and Davis Shores on the other side. The layout was basically square with four rooms on each of the two floors. The large wooden front door opened into a foyer. On the left of the foyer, along the wall, was a flight of steps leading to the second floor. Centered in the wall to the right was a door that opened into a parlor. One walked straight through the foyer to the dining room and turned right to get into the kitchen. The dinning room and kitchen, although as wide as the foyer and parlor, were not as deep. On the second floor, there was a railing around the stair opening, and a four foot wide hall that ran beside the stairway all the way to the front of the house. A sitting room had a door onto the overhanging porch. There was an entry door to both the front bedroom and to one of the back bedrooms from there. The entry to the other bedroom was through a door at the top of the stairs. At this same landing was a door to the bathroom. The bathroom had been added to the block-like architecture. It protruded out from the house and sat above a side porch. |

|

On the right (north) side of the house was a large yard, and there was a smaller yard to the south. This yard was quite shady because of a large tree, and the porch had a double wide swing. A driveway ran next to the south property line on the left and led to a garage.

The back yard was quite large, but unlike the side yards, it did not have grass. An area fenced off with chicken wire was always referred to as Minnie's Garden. Minnie (Amelia Pacetty) was Nellie's sister who was born in the house and had married Thomas Dowd. The Dowds lived in several places, but often were residents at 56 Marine. When Thomas died in 1922, Minnie moved back permanently. Sonny Kirkman remembered the flower beds in bad shape during his childhood, and imagined Minnie had become too frail to tend them. In the corner of the back yard was a large shed where Harry kept his ladders and various other painting supplies. Sonny wrote, "I was very young when he died, but one of the few things I remember about him was that he road a bicycle everywhere he went. I never asked and no one ever told me but there is no way he could have carried those ladders on a bicycle." There was another shed, much wider than it was deep, on the left side of the back yard that was actually four sheds built together, each with a separate door. There was a single seat swing in the back yard as well as an outhouse. The outhouse had been modernized with a regular flush toilet. |

|

The house had hot water heat with stand-up radiators in the various rooms. As the original structure was modified and added on to, there was no way to conceal the pipes running between the radiators because of the solid coquina walls, so they were exposed in parts of the house and painted to match the walls. The boiler was in a corner of the kitchen and was gas-fueled. The stove and refrigerator also ran on gas. There was a meter in one corner of the kitchen that the family had to put quarters into whenever the gauge on the front indicated that it was time for more gas. The water throughout the house was from a neighborhood artesian well. Unlike a surface well which required a pump to draw water out of the ground, the artesian well was so deep that the water was under pressure and came out of the ground without pumping. The artesian water in Florida was commonly known as sulfur water, because of the distinct taste of sulfur.

The bathroom had a bathtub that had four legs. There was no shower. There was cistern to catch and hold rain water. This was a large wooden tank, four feet in diameter, mounted in the corner where the bathroom joined the house. Because artesian well water was very hard, it did not dissolve soap very well. Soft rainwater flowed through one of the spigots in the sink for washing the hands and face. The Jones' had two telephones. One hung on the dining room wall and had no dial because Saint Augustine didn’t have a dial system. To place a call, one picked up the earpiece and spoke the number to the operator who answered. Their second phone was a table model that sat upstairs. The mouthpiece was at the top of a pedestal while the earpiece hung on the side. Their phone number was 154J. In the forties, the Jones' had an African-American maid named Lily. She would walk to the house in the morning and stay until around three o’clock when she would then walk home. She was responsible for the main meal of the day at noon. The three FEC workers would come home on their break and eat with the visiting Kirkmans in the dining room, while Lily took a tray upstairs for Minnie. Before Lily went home, she would create a simple dish from leftovers that Mabel and Bunny could heat for supper. A hired woman also came once a week to wash clothes. In the area behind the swing, there was a table made of boards across two sawhorses, some galvanized tubs, and a washboard. A big tub sat on a grill to allow the washwoman to build a fire and make hot water. She would add soap and bleach to the tub of hot water to do the bed linens and towels. She would use a big stick to stir the items like the agitator in a modern washing machine. After the washing was done, she hung everything on the clothesline to dry. Several things changed for the Kirkmans in 1940. For one, their third child, Ann, was born in February. When they visited Saint Augustine that summer, they discovered that Bunny and Fleming had planted Saint Augustine grass runners all over the backyard. It spread rapidly and dramatically changed the appearance of the yard. Harriette, who had been raised in a dirt yard was greatly surprised by the change. The two swings in the yard and the one on the upstairs porch were primarily for Old Lady. During the warm weather she spent most of her time on her swings. From the upstairs swing she had a view of the Matanzas River and since it was a part of the inland waterway, she could watch the yachts pass by. She could even see the Bridge of Lions, a drawbridge, as it opened to let the larger boats through. Many people walked along Marine Street, and Old Lady knew everyone that lived on the street, and they all knew her. She would yell a hello to neighbors and they would often stop and speak with her. Old Lady would be in the swing in the side yard on the day the garbage man would come, as well as when the swill man—a local pig farmer—would come. Washday was a big day. Old Lady would be in the swing in the backyard by the time the washwoman got there and would watch her do all of her work. The woman would have all the clothes on the clothesline by lunchtime and after the meal, Old Lady would go back to her swing. Every now and then she liked to walk to the clothesline to check on whether the clothes were dry. Once dry, she would take them down from the line and put everything in a basket. Lily was usually still there when the clothes were all down and would help bring them in the house. Then Old Lady would sort and fold each item. The Cathedral Basilica had a clock tower that tolled out the time on the hour and then rang a single toll every half-hour. One could hear it all over town. There was also a clock in the foyer of the house at the foot of the stairs that chimed the hour and half-hour. This was a tall clock that was wound by resetting two heavy weights on chains inside the glass portion at the bottom of the cabinet. It was much like a grandfather clock and was acquired by Nellie who saved Octagon soap wrappers to win it. Old Lady knew how to read the time on a clock, but she used the Cathedral bells to keep track of the time when she was outside. When it struck twelve, she headed for the dining room, as she knew Fleming, Mabel, and Bunny would be home in ten minutes. Quite often, she would have a story to tell us that she had heard from one of the neighbors, or based on something she had observed during the morning. When the weather was cold, Old Lady did things in the house. Her prized possession was her dollhouse, which was actually just a box of pictures cut from magazines. She would find pictures of houses or rooms that she liked and then have someone cut them for her with scissors. If she found a specific item that she liked—such as flowers, a piece of furniture, a person, or any item that she thought would look good in one of rooms—she would paste it on the picture. This was an incredible feat of memory, as she had mentally cataloged all of her houses and rooms to know how to furnish them. Often, Old Lady would sit in a rocking chair and look at one of her pictures for a long time. Minnie helped Old Lady do many of these types of things. She also helped her with other crafts. Harriette brought Old Lady sewing cards, which were designed for small children. These were pieces of stiff paper with a connect-the-dots picture that the one would create with colored yarn. Minnie's room was at the top of the stairs, and Sonny remembers it as being dark and foreboding. She had a large bed in one corner and there was a table in the middle of the room. The only light was a bulb with a simple reflector that extended down from the ceiling over the table where she sat most of the time. Minnie often wore a green eyeshade visor, suggesting that she might have suffered headaches from bright light. When the children visited, Minnie played simple games with them like old maid, checkers, Chinese checkers, and dominoes. She showed them how to play solitaire and she also would tell fortunes with playing cards. Sometimes, if Minnie had a cup of hot tea, she would tell fortunes by reading the tea leaves left in the bottom of the cup. She owned a Victrola and a collection of 78-rpm records by musical luminaries from the twenties and thirties, including Enrico Caruso. The Victrola was a table model and sat on a table in a corner. It had a lift-up lid that exposed the turntable and needle. In the front, there were two small doors that opened to let the sound out. A crank on the side wound the motor. Nellie Jones used to walk into town to pay the electric bill and go to the bank. Sonny would walk with her if it meant passing Hamblen’s Hardware store. Hamblen’s was unlike any store Sonny had ever seen. He was fascinated by the woodworking tools displayed behind the large storefront windows. On several occasions, Sonny and his grandmother went inside, probably to pay the family's bill, since Harry bought all of his painting supplies at the store. The lighting at 56 Marine was poor. The whole family stayed upstairs after dark and the children were afraid to go downstairs alone at night. Walking on the street at night was equally scary because there were few streetlights and those that existed put out little light. In the forties, Saint Augustine was still a very small city and you could walk to most of the historic places of interest. The Kirkmans were both locals and curiosity seekers during their summer visits. For the children, the first trip to the fort, the resort hotels, the old houses, and the museums were all memorable experiences. They lived in a neighborhood adjacent to the historic center of Saint Augustine and thus had little experience with the modern city that was expanding to the west. |

|

The Oldest House was located just around the corner of Marine Street, about three quarters of a block from the Jones house. Old Lady waved to tourists in horse drawn carriages making their way along Marine Street. In the center of the downtown area there was a large plaza with benches, palm trees, and live oak trees. The historic market is located at the east end of the plaza. The market was an open structure with a roof, which served mainly as a place where older citizens went to talk, read, play checkers, or cards. At the other end of the plaza was Saint George Street with the building that served as the post office across the street. Along the north side of the plaza was the Cathedral and rectory. In that same block was the newest and best of the two movie theaters, which the Kirkmans attended many times during each summer.

Going north up Saint George Street were most of the retail stores, including two five and dime stores. Saint George ended at the original city gates that at one time had been an entrance to the walled city. From the city gates, one could see Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) overlooking Matanzas Bay. Nellie told Sonny stories about the how the fort was used while she was a child and how the Indian leader Geronimo had been imprisoned there (which she likely believed, but was not actually true). Within a couple of blocks from the downtown area was the Ponce de León Hotel, which was still operating in the forties, but only during the winter months. The Kirkmans had occasional opportunities to tour the Ponce de León, and see gravity fed flush toilets in each of the rooms. The other once-famous hotels were no longer open. The bottom floors were used for retail or, in some cases, museums. The city pier was a small pier primarily used for yachts to dock and refuel. There were also a number of cabin cruisers, owned by local people, tied up there. Between the city pier and Fort Marion was the Bridge of Lions, a drawbridge that crossed Matanzas Bay and Highway A1A—the coastal highway that ran along the ocean down the east coast of Florida. The bridge provided access to Davis Shores, where many people lived, and to Saint Augustine Beach. Lighthouse Park was also on the east side of the river, where there was an operating lighthouse and a fishing pier on a small body of water called Salt Run. About twelve miles further south was Marineland, the first seawater aquarium in the country. Saint Augustine was practically surrounded by water. Off of the southern part of the bay was a tributary called the San Sebastian. It curved around the southern part of the city and ran along the western edge. Along the San Sebastian were boat yards and a large building where the shrimp boats would unload their catches. This was very near the FEC Office and the FEC Hospital. Commercial fishing was one of Saint Augustine's few industries, and the shrimp boats would pass within view of the Marine Street house and then through the Bridge of Lions on their way to the Vilano Inlet and the Atlantic Ocean. At least once each summer—and sometimes more than once—the Kirkmans would take Nellie to see very old friends that she had known most of her life. The children protested, but Old Lady enjoyed every minute. It was a errand made easier when Harriette was in town, since Mabel and Bunny worked during weekday visiting hours. Nellie dressed up, complete with a hat, gloves, and sometimes a parasol. Old Lady would sit and listen to their conversation, while Harriette, and sometimes young Shriley, would try to participate. These trips mostly involved two of Nellie’s cousins—children of her Uncle William F Monson—in Mandarin, Florida, about twenty-five miles from Saint Augustine. Old Lady loved the drive. One of these cousins had a beautiful home on the Saint Johns River, with a large yard shaded by live oak trees and Spanish moss. Nellie also loved to go to the La Leche shrine, located in a park on the site where Pedro Menendez de Aviles landed in 1565 and founded Saint Augustine. The visit required driving down a side street with trees and Spanish moss. The path walked guests through the oldest cemetery in the city. Sonny remembers a large steamer trunk that lived in the upstairs sitting room at 56 Marine Street. Because it had a flat top, it served as a table and had various things on top of it. The trunk contained old jewelry, coins, pocket watches, pictures, and all sorts of family memorabilia. Once during every summer, the children would ask Nellie to open the trunk and tell stories about the items and who they had belonged to. Over the years, the family went to Marineland a number of times. Old Lady enjoyed these short trips too, and she and Nellie were satisfied to sit in the car with a good view of the people entering the gates. The children watched the porpoises perform, looked at all the different species of fish through the windows of the large tanks, and saw men in diving gear feed them. This was not scuba gear, but suits with large steel helmets attached by hoses to an air pump above the water. Sometime in 1940, Mabel bought a beach house. Bunny bought the lot on one side of it and Fleming bought the lot on the other side. The house was in poor condition, but Fleming and another man who worked at the FEC completely renovated the interior. The beach house was located north of Vilano Beach on US Highway A1A. Easiest access to the beach was via the Vilano Bridge, well north of the city. At that time, the structure up to the draw gates was wooden, but the remaining span had been rebuilt in concrete. The bridge was a popular fishing spot. Vilano Beach was a very small community of beach houses, with several structures on the ocean side of the highway, but hardly any on the river side. There was one convenience store on the corner. The entire community went no more than three-quarters of a mile up the highway. After that, there was nothing on either side of the road, not even telephone poles, since electric power ended at Vilano Beach. About another two miles up the highway was a road about a quarter of a mile long, made of crushed oyster shells leading down to the North River. At the end of the road was the home of Captain Frank Usina. He ran a sightseeing boat that he kept tied up at a small pier on Bay Street in Saint Augustine. The family had known the Usinas for many generations. They had a small pier at their location on the North River. Continuing up A1A another short distance was a gas station and a fairly large bathhouse on the ocean side of the road. The bathhouse had not been used for many years, but in the early 1900s, the Usinas had developed the property into a recreational area. At that time, there was no road leading to North Beach. The Usinas would bring people in a boat to their place along the river where they would have a big cookout. There was a railroad track from that location to the beach. They used a horse-drawn train to then take people to the bathhouse where they could change into their swimming clothes. By 1940, the tracks had been removed many years before, but the bathhouse remained. The little gas station was built many years later. It was still operating in the forties, and was quite interesting. Since there was no electricity, there was a long handle on the side of the gas pump to pump gasoline by hand into a glass cylinder. It was marked so that one could pump the amount of gas you wanted to buy. It then was gravity fed through the hose into the car. |

|

About a quarter mile further up the highway was Mabel's beach house. It was built on stilts with an enclosed two-car garage under the house. The exterior was clad in asphalt shingles. There were stairs on the right side leading to a very small foyer. Inside, a room that served as the dining area and the living room went from back to the front. The kitchen and a small hall led past the bathroom and to a single bedroom. Across the front was a porch two steps lower than the living room. The porch had low wooden walls, about three feet high, and screen wire to the ceiling. Several years later the screened portion was replaced with windows. On the porch was a swing at least eight feet wide, and four feet deep, with a cushion eight inches thick. At the other end of the porch was a door that opened onto a small landing with three steps to get down to the front yard on the beach side, which was just white sand. The front yard was twenty-five feet wide and was roughly fifteen feet above the beach elevation. A wooden walkway took one to the beach.

In the garage, Fleming stored his tools, paint, ladder, and other things he could need to maintain the place. On the other side of the garage was a shower stall and dressing room. There was no electricity, telephone, or water at the beach house. The garage contained a surface well with a manual pump, a gasoline engine with a generator, and two twelve-volt car batteries. The pump had a large pulley on it, as did the gasoline engine, so with a belt between the two, the engine would run the pump. The two car batteries supplied the power to start the engine and were charged when the engine was running, like an how alternator charges batteries in a car. On the roof of the house were four fifty-gallon barrels. Water was pumped into these barrels to provide gravity fed fresh water for the kitchen, the bathroom, a spigot on the stoop by the porch, and the shower in the garage. There were two wall mounted light fixtures along the wall in the dining room, one ceiling fixture in the kitchen, and one in the bedroom. There was also a light over the entrance to the house on the highway side. These were all twelve volt lights and ran off the car batteries in the garage. The family carefully monitored their use to protect against exhausting the power supply. A wall mounted kerosene lantern in the bathroom burned all night. There was an icebox which held a fifty-pound block of ice, and a kerosene stove with four burners and an oven. During the summer of 1941, the family only went to the beach house on the weekends. Fleming drove a Plymouth and Mabel and Bunny shared a Pontiac—both were probably 1939 models. These were large vehicles that could seat three people on the front seat and four in the back. Fleming would use his car to take Mabel and Bunny with him to work at the FEC. That left the Pontiac for Harriette. On Friday afternoons, the FEC crew came home from work at 5pm. The entire family would load up the Pontiac with the boxes of food and supplies needed for the weekend. The Pontiac would go straight to the beach house and start unloading. Fleming and his passengers made a stop at the ice house to get a block of ice. During this first summer at the beach house, Harry, Nellie, and Minnie stayed on Marine Street. The two recreational activities that Fleming really enjoyed were fishing and bowling. Mabel had no interest in such things, but Bunny and Fleming went bowling during the winter months, and fishing during the summer. On several weekend afternoons, they took Sonny Kirkman fishing off the Vilano Bridge. Fleming would also surf fish in front of the house and they would all go crabbing. Since the family knew the Usinas, they would go to their small river pier just down the road. Crabbing was easy and fun. One just tied some meat on the end of a cord and lowered it to the bottom of the water. After five or ten minutes, several crabs would be hanging onto the meat could be scooped up with a basket-like net on the end of a long pole. The catch was taken back to the house to be boiled. Harriette, Mabel, and Bunny would sit at the table, crack them open and dig out the crabmeat, which was mainly in the claws. They would make crab salad, which they all loved. The Kirkman family played on what was nearly their own private beach. It was rare to see anyone so far from civilization. Pelicans flew by the house, headed either north or south, flying in single file with as many as twenty in the squadron. This occurred every thirty minutes or so. The birds flew low over the shoreline and when the lead bird flapped its wings, the others would flap theirs, one at a time, all the way down the line. As soon as the leader stopped and glided, the others did the same. On Sunday morning, Fleming, Bunny, and Sonny went to the early mass at the Cathedral in Saint Augustine. When they returned, Harriette, Mabel, Shirley, and Ann went to a later morning mass. Then on Monday morning, Fleming, Mabel, and Bunny would leave for Saint Augustine early enough for them to get to the house and get ready for work. Harriette would transport the rest later in the morning, so that everyone was together for lunch. |

|

The Kirkman's 1942 vacation to Florida was nearly disrupted by the attack on Pearl Harbor at the US entry into the war. But Harry Jones became very ill that year, and TC Kirkman decided the family needed to be together. He wrote of the situation :

"My reason for not wanting them to come down was largely because of the war situation. I have believed for some months that one of these days there will be a token attack by the Germans on the Atlantic Coast, either by fire from a submarine or by bombing from a plane, and I can think of no better place for such an attack to be made than the Florida Coast, although the area in the vicinity of Palm Beach would be the most vulnerable due to the fact that the main channel of the Gulf Stream is only a half mile off the coast there. Of course, the chances of being involved in any such attack would be remote, it could happen." Probably before TC's letter even got to Saint Augustine, there was a long distance call from Bunny saying that Harry was dying and Harriette should come as soon as possible. They made fast arrangements and all arrived together on Saturday, April 18, which was reported in the Saint Augustine paper. Harry suffered kidney failure and died the following Wednesday, April 22. He was only sixty-nine years old. The funeral was on Friday and the Kirkmans returned home on Saturday. The Kirkmans traveled to Saint Augustine the later part of June as had been planned before Harry died. The mandatory blackout up and down the east coast that TC had mentioned in his letter in April never went into effect, because the US government felt it would show of fear to the Nazis. Over the winter, Mabel had bought a Pomeranian dog named was Mitzi, who she thought would comfort her after her father's passing. Mitzi was a small dog who but didn’t pay much attention to anyone except Mabel. They had their breakfast together, and Mabel gave Mitzi coffee and toast. Harry Jones had bought a plot at San Lorenzo Cemetery for the entire family. It was a large rectangular shaped area marked of with a granite curb. It was designed for eight caskets. During this summer of 1942, a routine was developed around taking zinnias to the cemetery. A woman that lived on a back street near the river grew and sold flowers. Old Lady and the children called her a witch because of the spooky place where she lived. At the cemetery, there were two graves with headstones. One was for Minnie’s husband Tom Dowd, and the other for Harry. Nellie’s father and mother were buried in a different section of this cemetery. While Harriette never remembered where the graves were located, Old Lady would give circuitous directions. Sonny suspected that Old Lady knew exactly where they needed to go, but just wanted to drive all around so she could see what was new. The family went to the cemetery several times during the summers spent in Saint Augustine. The war had a limited impact on Saint Augustine except for gas rationing and other scarcities. At the beach house, however, two Coast Guard sailors could be seen walking the beach from their station, two or three miles north, to the Vilano inlet. Then they would turn around and walk back. This was repeated all night. Fleming got in the habit of making a thermos or two of coffee for the guardsmen and he would put it with some cups at the bottom on the stairs that went down to the beach. On several occasions, they came up to the house to thank us for the coffee. In 1943, the coach cars from Jacksonville to Saint Augustine were packed with people, many of them servicemen. The luxury hotels were now training grounds and barracks for the US Coast Guard. The Ponce de León provided room for a Coast Guard boot camp. At any given time, as many 2,500 men were stationed here in the most opulent of all training camps. Matanzas Bay filled with zigzagging boats on maneuver. The cadets patrolled the beaches in search of enemy saboteurs or spies who might make landfall. German submarines cruised Florida shores, and the threat of enemy infiltration was real. Locals feared that the Coast Guard presence could draw Saint Augustine into actual fighting. The side street next to the Ponce was strung with clothes lines with shirts, blue jeans, and underwear hanging to dry. It was a striking sight to see on the magnificent hotel. Where previously there had been tourists milling around the grounds of the Fort, there were cadets marching. The sailors still patrolled the beach near the beach house, except that they rode horses. They still stopped for the coffee that Fleming would put out. Back on Marine Street, Minnie was bedridden. She suffered from breast cancer that allowed her good days and bad days. The children would occasionally be allowed to go into her room and talk to her while she was in bed, but for the most part, the rule was to not disturb her. Quite often, Minnie would scream out in pain. A doctor visited often, but her only treatment was morphine. Now nine years old, Sonny began writing letters to his father in High Point, and would anxiously wait for his reply. There was no local delivery in Saint Augustine, but a box at the post office. The Jones' number was 447, and Fleming's was 581. Sonny would walk to the post office twice each day, once in the morning and once in the afternoon when it seemed time for me to get a reply to a letter he had written. Harriette took Sonny and his sisters to Usina’s pier to go fishing. This usually happened on Monday after the others had left the beach house to go to work. They fished with hand lines from a pier that wasn’t very long. It had steps that led down to a lower smaller pier, very close to the water, that was so rowboats could tie up to it. There was rarely anyone else there. In a letter to his father, Sonny describes catching two toadfish while Harriette caught a typewriter (which was old and no good). Harriette would take Old Lady, Nellie, and the children to the movies after lunch. She would come back after about two hours, come into the theater for Old Lady and Nellie and take them home. The rest usually stayed until five o’clock. Each day, Mabel, Bunny, and Fleming stopped at a drug store on their way home from work for a cup of coffee. The drug store was a block from the theater, so the children would walk over and meet them, sometimes having a drink or ice cream. In 1944, Sonny went down to the beach by himself and stepped on a skeleton of the head and dorsal fin of a catfish buried in the soft sand. The fin went into the bottom of his foot close to my toes and stuck all the way through. The options for such an injury in most households at the time was either Iodine or Mercurochrome. But the Jones family had neither. Instead, they used a medication called Freezes. Unlike Iodine or Mercurochrome that were red and watery, it was a clear mixture and a little thicker. When Sonny got to the house and explained what had happened, Nellie decided right away that the wound wasn’t appropriate for Freezes. She put kerosene in a pan and had the boy soak his foot in it. It healed in just a few days. When the visiting the cemetery that year, there were now three graves in the family plot, Tom Dowd, Minnie Dowd, and Harry Jones. Minnie had passed in October, and Harriette had been informed by mail. Given the war restrictions on travel, she was unable to be with her aunt in her final days or attend the memorial. An artesian well added at the beach house in 1945. Workers used a large tower to drive four-inch pipe into the ground adding a new one when the previous was flush with the ground. With the pipes in the ground, they began drilling until water could be seen spilling out over the top. Eventually, there was a two-foot high column of water shooting out of the pipe, like a miniature oil. Once capped, Fleming and Sonny dug a trench to the garage, laid pipe and connected the well to the plumbing in the garage. In the summer of 1946, the military had left Saint Augustine. The Ponce de Leon hotel was closed, and it looked like it had taken a beating during the previous few years. Coast guard sailors no longer patrolled the beach, and the tourists were once again all over town. With gas rationing a thing of the past, Fleming and Bunny took the Kirkmans to Jacksonville Beach on a Saturday night. In the coming years, they would go there once during each summer. Jacksonville Beach had a boardwalk, a pier, rides, and booths with various games. The kids would ride the Ferris wheel and the merry-go-round. They also made a shopping trip to Jacksonville at least once each summer. There was a large department store named Cohen’s near the Roosevelt Hotel. They would park in the hotel’s parking lot and Old Lady and Nellie would sit in the hotel lobby and watch the people, which was one of Old Lady’s favorite things. The family would spend a lot of time at Cohen's and one person would go and check on the lobby every so often. No one seemed to object the pair sitting there. July fourth fireworks from the Fort had been curtailed during the war, but started again in 1946. The family watched from the plaza, though they were quite visible from the front porch of the house as well. Old Lady and Nellie watched them from there. Fleming had got a new apartment directly across the street from the Jones house. It was on the second floor at the back of the house, which a front facing on Bay Street. Fleming's unit had its own set of steps up to a porch with a private entrance. He had only a small sitting area, but a fairly large bedroom with two beds, and a bathroom. Sonny started sleeping at Fleming's place just to make more room at the house. At the beach house, Sonny made a kite with heavy brown paper. Fleming made a reel so he could crank the string in rather than have to just wind it up. It flew so well that Sonny needed an additional ball of string so he could let it fly out further. One day Fleming asked Sonny if he wanted to send a message to the man in the kite. He took a piece of paper about three inches square, wrote “Hello” on it and punched a small hole in its center. Then he untied the string from the kite and put the string through the hole in the paper. After attaching the string back to the kite, they let the kite lift off holding the piece of paper as the string went through it. Once the kite was up very high, he told Sonny to let go of the little piece of paper. When he did, the paper started walking up the string. By 1947, power lines ran up Highway A1A and the beach house had electricity. The icebox was replaced with a refrigerator and the kerosene stove with an electric stove. They decided against a hot water heater, so the showers were still cold as ice. Electricity meant the Jones' were able to do more things at night. Playing cards became a routine, including cribbage. It is a game for two people that Harriette and TC had played it before they were married. Hearts was a favorite when three or four people were interested. They also got caught up in a national craze called Canasta. It was played with two decks of cards, and stores started selling Canasta cards, which were two decks of standard playing cards with identical backs. Fleming, Bunny, and Sonny played cards more than the others, but Shirley often played, too. As Ann got a little older, she became a major member of the card-playing group. Fleming had a new car in 1947 as well. It was a Buick he had ordered in October of 1945, but didn’t receive until November of 1946. Fleming had a cousin named Daisy who lived in Denver. Although they stayed in touch, he had not seen her in a long time. With his new car, he decided he would drive to Denver and he wanted Mabel and Bunny to go with him. Harriette encouraged them all to take the trip while she was in Saint Augustine and could take care of Nellie and Old Lady. It was then decided that Sonny should go with them. The Kirkmans visited Saint Augustine again at Christmas in 1947. Harriet travelled with the children as soon as schools were closed, and TC joined them on Christmas Eve. For the first time, the train was pulled by a diesel locomotive which were starting to be phased in on all railroad lines. Diesel engines were very colorful, being painted with the colors adopted by the various railroad lines. They had a second headlight mounted above the regular headlight. Its reflector rotated on an off-center shaft so that the light beam formed a figure eight in the sky. At night, while waiting for a train to come into the station, the first thing one would see was this light beam flashing the figure eight pattern in the sky. Harriet took Old Lady, Nellie, and Sonny to cut down a Christmas tree. Nellie said she knew a spot. Although you could buy a cedar or spruce tree that was shipped in at Christmas time, there were none growing around Saint Augustine and pine trees were commonly used as Christmas trees. Nellie led them to an area with pine trees. After looking them over, Sonny cut one down. It was bigger than it should have been. They had a terrible time tying it to the car, and had to trim it down to a useable size at the house. Sonny remembers it as the ugliest Christmas tree there has ever been. Even with the ugly tree, they had a great Christmas. Fleming and Bunny got Sonny a fishing rod and reel. It was a fairly short steel rod with an inexpensive level winding reel. |